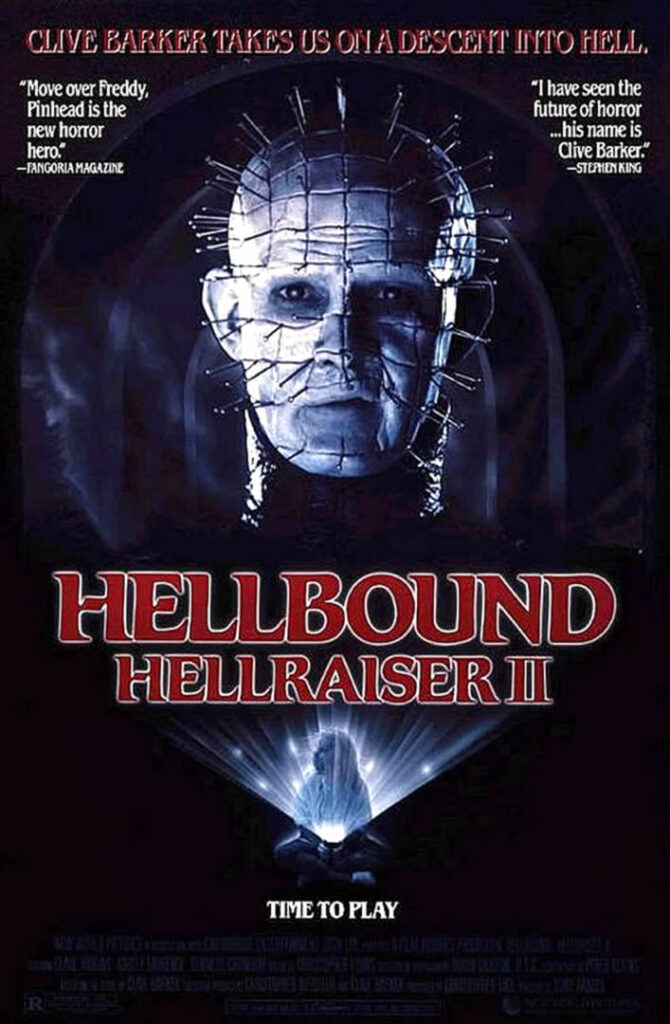

HELLBOUND: HELLRAISER II (1988)

(Note: this text was published 12 years ago on my former blog, Cinematic Nightmares)

HELLRAISER is rightfully considered one of the best horror films of the 80s. The film was a great success which lead to a sequel a year later titled HELLBOUND: HELLRAISER II. It shares most of its creative team with the first film (producer, cinematographer, set designer, makeup creator, composer), as well as production companies (Film Futures and Roger Corman’s New World Pictures). This time, the director is Tony Randel, with Peter Atkins as the screenwriter, while Barker is the author of the story. Though the lineup alone doesn’t always guarantee success, in this case, the film fulfilled the expectations of the fans.

HELLBOUND picks up where the first film left off. Kirsty (again played by Ashley Laurence) is in a psychiatric institution, recovering from the previous events. The institution is run by Dr. Channard (Kenneth Cranham), whose main interest lies in exploring further regions of human experience. After meeting Kirsty, he realizes he is on the verge of fulfilling his insterest. In his pursuit, he doesn’t hesitate to use his own patients to resurrect Julia (once again portrayed by Clare Higgins), in an extremely bloody and well-executed scene that surpasses most of the gory scenes from the first film.

Meanwhile, Kirsty befriends hospital worker Kyle (William Hope) and patient Tiffany (Imogen Boorman), whose puzzle-solving abilities Channard had already tried to exploit for his research. Kirsty receives a message from her father (later revealed to be a false message), begging her to rescue him from the depths of hell. Determined to help him, she teams up with Kyle and Tiffany. Channard, realizing he’s on the right path, uses Tiffany to solve the puzzle box that summons the Cenobites. The gates of Hell are now opened, and everyone goes inside. However, the rules of Hell differ from those of the outside world, and Kirsty and Tiffany must work together to escape the Cenobites.

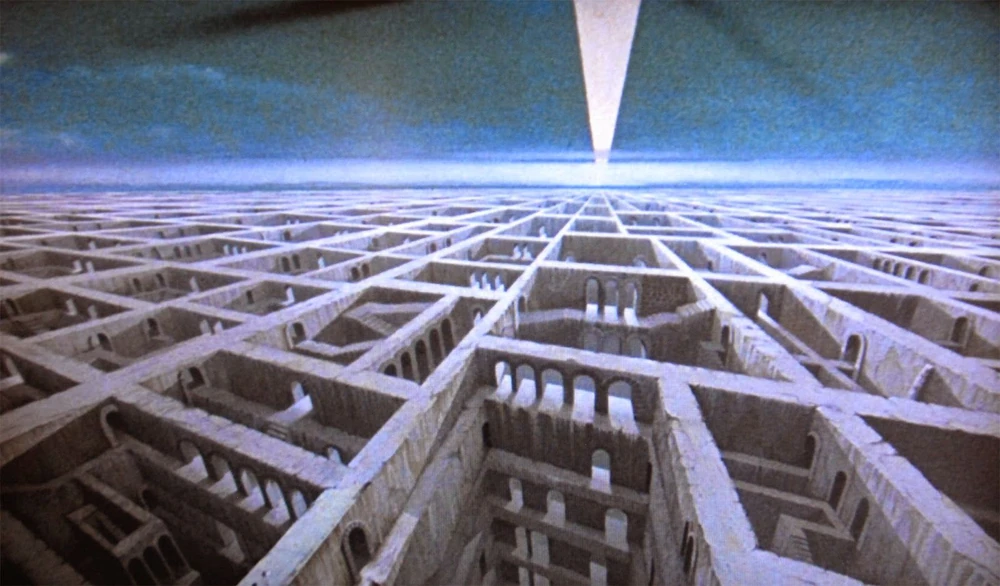

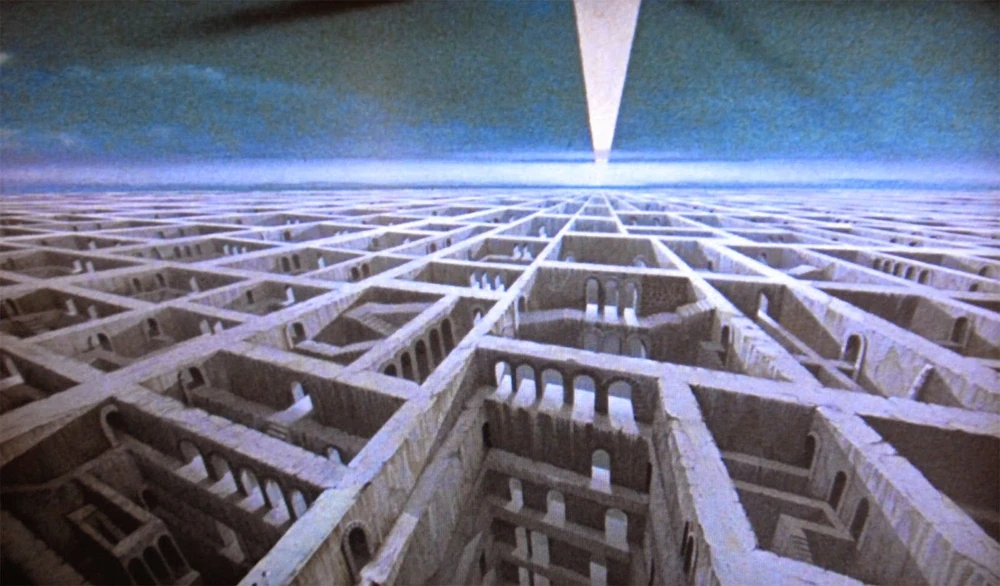

The depiction of Hell as an endless labyrinth reflects the story’s structure and the way it unfolds. Up until the characters enter the depths of Hell, the narrative is quite similar to the one of the first film. From that point, the film becomes something entirely different, adopting an almost chaotic structure, turning into a series of episodes involving characters running through the labyrinth and discovering new things in its rooms and corridors. This approach works, as the film doesn’t disintegrate into meaningless parts; it’s not just a random series of episodes. So, the fragmentation is justified, as the story takes place in a labyrinth, and the characters are portrayed in such a way that they would likely behave as they do in the given circumstances. There are several surreal, nightmarish visions that showcase immense creativity in their morbidity, explicitness, and constant sense of danger.

One of the main things that a sequel should fulfill to justify its existence is the meaningful introduction of new themes into the story of the first film. Obviously, one of the key innovations in this sequel is the depiction of Hell. Hell is not shown in a stereotypical way, full of fire, torture devices, and such. It’s a cold labyrinth, with individual rooms – dungeons, which, in line with the film’s philosophy, are both torture chambers and places of pleasure. It’s a realm of forbidden desires and hidden knowledge, inhabited by the Cenobites, who conduct their experiments on humans wait for a new candidates. At times, Randel even goes further than Barker did in the original, offering unforgettable horror scenes that imprint themselves into our memory. The film is soaked in a dark, sinister atmosphere, and Randel tries to follow the original in this regard (and succeeds), never giving the viewer a moment of rest. There’s a new surprise waiting around every corner, especially in the second half of the film.

The visual effects are excellent and are worth every penny (the concept of Hell itself, the individual dungeons, Leviathan). Atkins’ screenplay is very engaging, but a few inconsistencies and plot holes might bother some viewers. That becomes the most evident in the second half of the film. One of the most glaring examples is the fate of the protagonist’s father, who, after the false message to Kirsty, is never mentioned again. This was due to Andrew Robinson refusing to reprise his role, even though his character had already been written into the script, leading to the introduction of the false trace. But this leaves a gap in the story.

The characters are mostly well-developed, with Dr. Channard as the most interesting one, his cold expression radiating his determination to reach new regions of human experience. One of my favorite scenes in film history occurs when Channard emerges as a Cenobite from the transformation chamber and, gazing over the landscape with his new eyes, declares: “And to think… I hesitated.”

Julia is portrayaed as a queen of Hell in a way, seducing Channard and leading new victims into the labyrinth of the Lovecraf-inspired entity Leviathan, God of Hell. Clare Higgins once again delivers a great performance. Ashley Laurence is quite good, as she was in the first film. Imogen Boorman also does a fine job, even though she isn’t given much material, but she still manages to navigate through her character’s stages of development.

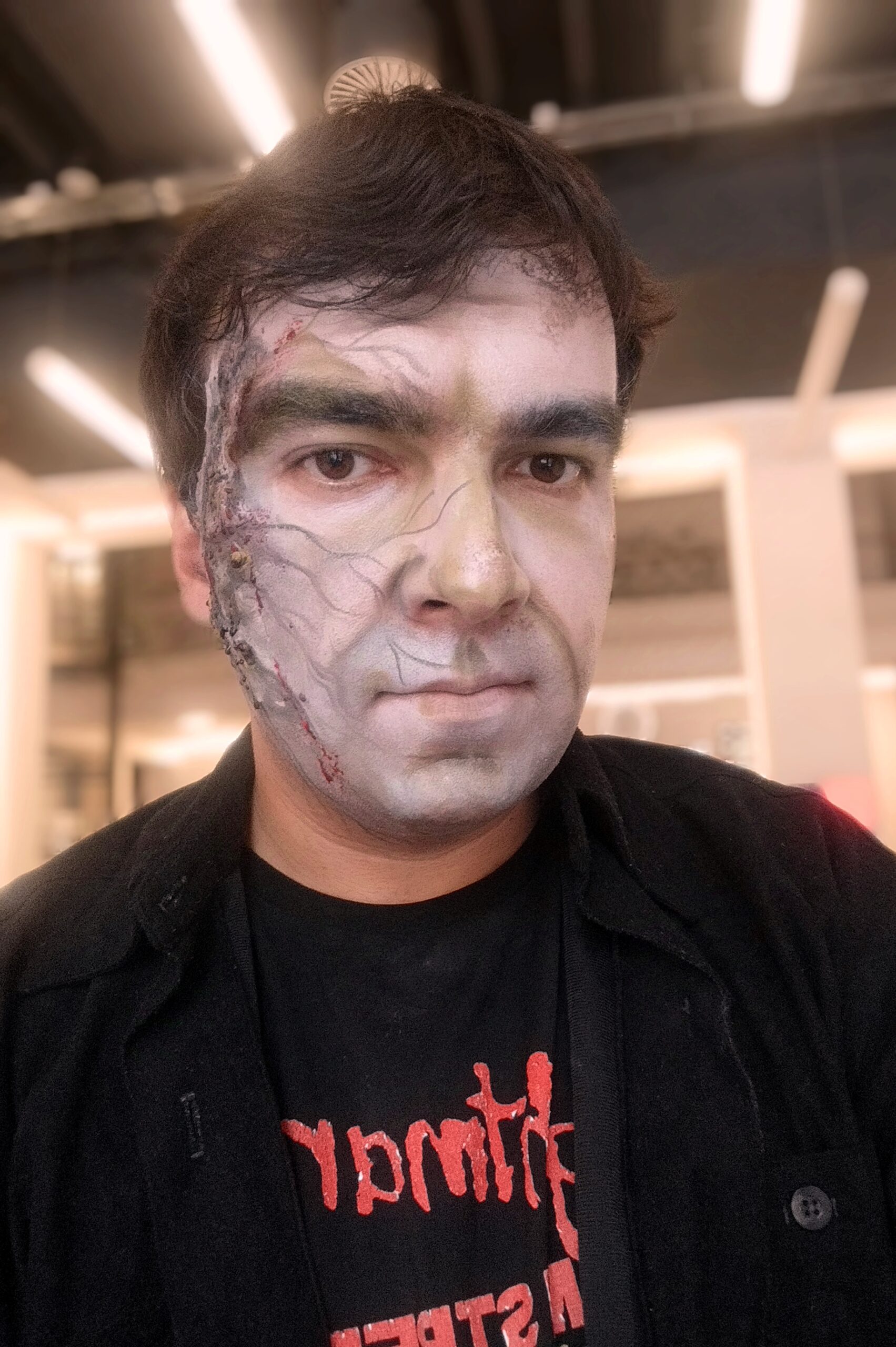

As for the Cenobites, they are portrayed perfectly in most scenes as demons of human flesh, lurking in the shadows (most of the actors who portrayed Cenobites reprised their roles, except for Grace Kirby, who was replaced by Barbie Wilde as the Female Cenobite). However, they change from the initial portrayal into something else at the end of the film, and that’s where the main problem arises – their unnecessary humanization, which can be considered the film’s biggest and only true mistake. Once humans (we see the creation of Pinhead early in the film – Doug Bradley plays a British soldier seeking to explore the further regions of human experience), and then demons for a long time, they recall their humanity in a pointless scene near the film’s end, which alters them both physically and mentally. This shift in the film’s rules weakens the film – without it, the film would have been even stronger and would likely surpassed the original. HELLBOUND introduces new elements to the story, along with new script and directorial choices, but veers in the wrong direction by humanizing the Cenobites. The transformation scene of Dr. Channard into a Cenobite – a man into a demon – can be seen as a precursor to this act, but it fits the film naturally as it’s the continuation of his quest for the further regions of experience. Thus, it wouldn’t have stood out even if the Cenobite humanization had been omitted.

The music is once again composed by Christopher Young, and I can only repeat what I said about the first film’s score – simply brilliant. The music for the first two HELLRAISER films showcases the full extent of Young’s talent. Sadly, Young is quite underrated as a composer, though he deservedly won the Saturn Award for the HELLBOUND soundtrack.

All in all, HELLBOUND is a film on par with the original when it comes to the overall quality, and it could have surpassed it with a few tweaks to the script and the removal of the humanization of the Cenobites.

Rating: 4/5

Leave a Reply