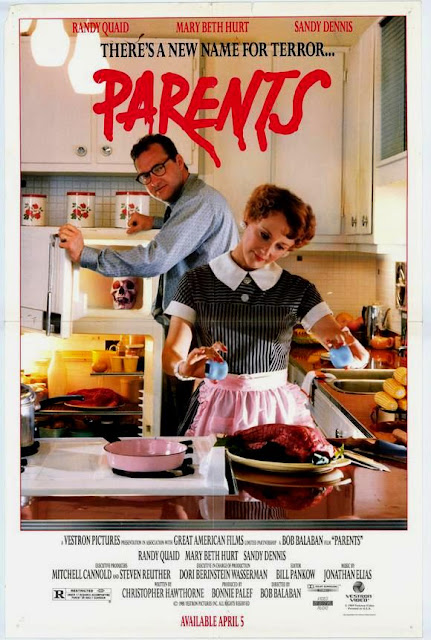

PARENTS (1989)

(Note: this text was originally published 12 years ago on my former blog, Cinematic Nightmares)

I watched PARENTS based on a recommendation, and I was glad that I wasn’t disappointed with this pretty effective horror-comedy. The film is directed by Bob Balaban (we know him as an actor from films like ALTERED STATES and 2010), with a screenplay by Christopher Hawthorne.

A new family moves into town – dad Nick (Randy Quaid), mom Lily (Mary Beth Hurt), and a son Michael (Bryan Madorsky). The parents quickly fit into their new surroundings, with the father excelling at work, but Michael struggles to fit in. Simultaneously, he is tormented by horrific nightmares, which apparently plagued him even before. His parents serve large meat-heavy meals every day, “leftovers from the fridge,” which is all Michael is supposed to know about it. However, he starts suspecting that the meat isn’t the animal one and that his parents might be cannibals.

Balaban is mostly interested in the portrayal of the family and the possible layers of darkenss beneath the seemingly perfect surface. The story is set in the 1950s, a decade that became synonymous with the economic prosperity and the baby boom generation in the USA. The ideal of the “American Dream” – ever-changing but often tied to economic success – seemed more tangible during this era, particularly for the middle and upper classes. At the center of all of this was the family, presented as a peaceful, prosperous entity, an ideal every average American should strive for in pursuit of the American Dream. But Balaban portrays this seemingly ideal family as parasitic, full of hidden darkness and subject to corruption of all kinds.

Most scenes are shown from Michael’s perspective, while others, especially those showing the family’s social activities – gatherings with friends and so on – mock the customs and behaviors of the time, using exaggerated orchestral music and acting. The “ordinariness” of the middle-class family is constantly ridiculed. This is clear from the first minute when they arrive in their new town.

Balaban doesn’t stop there and delves deeper beneath the surface. Through the early stages of his growing up process, Michael starts to think that his parents and the world around him aren’t what they seem. Something is being hidden from him. His parents are engaged in secret activities behind closed doors; his father works at a job in a factory that Michael doesn’t understand. Michael’s suspicions are mostly focused on the family itself, on the environment in which he spends most of his time. The film contains scenes hinting at the Oedipus complex, which may be one of the catalysts for Michael’s confusion. Here, the father is the primary threat – not just in a Freudian sense but also as a very real, physical danger to Michael.

During one scene, when Michael wakes up to get a glass of water in the middle of the night, he sees his parents “making love” in a very bizzare way on the living room floor. The way he sees this event, combined with his suspicions about cannibalism, might be seen as the product of a disturbed eight-year-old’s imagination. However, if we observe how the director depicts Michael’s family and their acquaintances, we’ll see that there’s truly something “rotten” going on there. Balaban paints a world where the middle and upper classes function by exploiting the lower classes and country’s natural resources. This is a world that, in its laboratories, creates poisons and atomic bombs, experimenting on human bodies and souls. The film exposes that dark underside, both on a broader societal level and within the family unit. Behind the facades of the line of houses inhabited by seemingly happy families, the worst kinds of crimes are committed, and obedient and faceless citizens are created with the help of other social institutions. Cannibalism serves as a metaphor for all these hidden family secrets.

The resolution of Michael’s suspicion about cannibalism at the end of the film isn’t handled in the best way, as the film mostly loses its dreamlike quality, though it doesn’t completely enter a “yes or no” territory.

One of the film’s themes is the role of leader and servant within the family, roles connected to the broader society. The father is the dominant figure here, the mother balances between her husband and son (having been “converted” by her husband), and the son is expected to accept everything as served and continue the family tradition. Throughout the film, it’s emphasized that Michael “isn’t like his parents“ (as his father says), which we can also link to the aforementioned childhood fears of growing up. Additionally, the older generation wants to pass on their behavioral patterns, customs, and norms to the younger generation without seeking their opinion – a process that occurs gradually. This is expected of Michael too. So, the roots of evil are situated within the family itself. The authority parents exert over their children is a target of a critique in this film, as well as any form of societal authority. There is a certain level of hope present for the younger generations and their desire and ability not to accept these imposed norms.

As Balaban’s directorial debut, this is a very skillfully directed film. The horror and comedic elements are mostly well intertwined, with the former being the stronger element. Balaban is energetic in conveying his views, fully focused on exposing the darkness beneath the seemingly polished surface of American suburbia but also never forgetting to be entertaining. In the non-horror scenes, he turns to parodying the everyday life of the middle class. The parallels between this film and David Lynch’s BLUE VELVET are obvious. Like Lynch, Balaban incorporates numerous surreal scenes that highlight the protagonists’ internal struggles, as well as depictions of a small American town, almost soap opera-like in its look. One criticism which is often mentioned against this film is the slow build-up. In my opinion, that’s not an issue here – on the contrary, this story requires such an introduction. Had the element of cannibalism been introduced earlier, the film’s fabric would have been damaged.

Balaban’s long career in front of the camera certainly helped him in casting choices and directing the actors. Randy Quaid is perfect as the authoritative father, the head of the family who cannot stand any dissent. His character is dark and creepy, and it feels like that darkness could break out at any moment. Mary Beth Hurt plays the caring mother, eager to help her child overcome the difficulties of adapting to their new environment, yet she shares her husband’s views on Michael’s future. Bryan Madorsky, as Michael, is mostly very good in his role – a boy beginning to understand that the world isn’t quite as he imagined it to be. Confusion, suspicion, and fear are intertwined within him, and Madorsky conveys it all very well in every scene he’s in.

Angelo Badalamenti’s orchestral score is fantastic and perfectly serves its purpose. Besides his score, there are numerous hit songs and rock ‘n’ roll tracks (like Dean Martin’s “Memoirs are Made of This“ and Sheb Wooley’s “Purple People Eater“) adding to the overall atmosphere.

PARENTS is a very good and unfairly overlooked film by a talented director.

Rating: 4-/5

Leave a Reply